Hot Off the Presses

12/7/2023

Faculty Spotlight: Dr. Matthew Leporati Brings His First Academic Book to Life

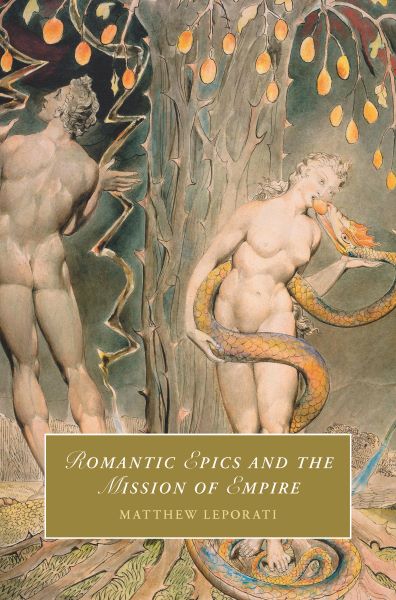

We’re delighted to share that Associate Professor of English Matthew Leporati, PhD just recently published his first academic book, “Romantic Epics and the Mission of Empire.” The book, a monograph published by Cambridge University Press, is now available for purchase and open access worldwide.

Take a look at the description:

“The British Romantic period saw an unprecedented explosion in epic poems, an understudied literary phenomenon that enabled writers to address unique historical tensions of the era. Long associated with empire, epic revived at a time when Britain was expanding its imperial reach, and when the concept of imperialism itself began to evolve into the notion of a benevolent project of spreading British culture and religion across the globe. Dr. Leporati argues that the epic revival not only reflects but also interrogates this evangelical turn. The first to examine the impact of the missionary work on epic literature, this book offers sustained analysis of both under-read and canonical works, bringing fresh historical and literary contexts to bear on our understanding of this unique revival of epic poetry.”

Back in 2021, Dr. Leporati teamed up with faculty colleague Professor of English Robert Jackolsky, PhD in authorship of a chapter called “Peeling The Onion: Pop Culture Satire in the Writing Classroom” in a collection that appears in the book “Isn’t It Ironic? Irony and Popular Culture.” The chapter is based on their use of satire in teaching the Mount’s ENGL 203 Writing Workshop, an advanced composition course offered every spring for select freshmen who are nominated by their ENGL 110 Writing in Context I instructors—as well as some upperclassmen who are English majors or writing minors. The chapter received fantastic reviews, and we’re sure Dr. Leporati’s first book will receive them as well.

We were lucky enough to sit down with Dr. Leporati to ask him a few questions about the project. Take a look at his reflection below.

Office of Public Relations [PR]: What inspired you to write this book? What kind of research went into it?

Matthew Leporati [ML]: “Romantic Epics and the Mission of Empire” began its life as my doctoral dissertation. So I’ve been working on this book in one form or another for about a decade! I was inspired to write it partially because I became fascinated by epic poetry as an undergraduate after taking a seminar in classical literature. Epics are, basically, long poems about heroes, and they are often thought to express the values of the culture and age in which they are composed (think Homer’s “Iliad” and “Odyssey” or Virgil’s “Aeneid;” in later eras, works like Milton’s “Paradise Lost” would be considered epic). When I started studying Romantic-era literature later in college and in graduate school (British literature from roughly 1789-1838), I became fascinated by the works of William Blake, who used a unique method of printing and visual art to create very unusual illustrated epic poems.

I began to notice that many of the well-known Romantic-era writers wrote epic poems, but they were often strange epics like Blake’s. For example, William Wordsworth used epic poetic devices to write a long poem where he recounted his autobiography, while Lord Byron published a satirical epic mocking many of his contemporaries, which he published in installments over years. So when I was in graduate school, I thought I could write my dissertation on the odd ways the Romantics used epic poetry.

When I started researching the lesser-known poems of the Romantic era, I was surprised to learn that more epics were written during this period than at any other time in history. Those famous poets and poems I mentioned earlier were actually part of a unique literary trend! But most of the lesser-known Romantic epics were not like the strange ones from Blake, Wordsworth, Byron, etc., which were all weird and unique (and interesting!): most of the lesser-known epics were much more conventional and straightforward (and, frankly, boring). A lot of writers wanted to imitate Homer and Milton and others, but most of them weren’t very good at it.

As I read more of these lesser-known epics, I noticed that many of them featured scenes of cultural contact, and even religious conversion. The well-known Romantic epics too often featured the idea of transmitting imagination or emotion, or of teaching or figuratively “converting” others. This got me thinking about the history of the period: the development of British imperialism and missionary work. So I started researching what missionaries were up to at the time, and lo and behold, I found that the Romantic era actually saw the beginning of the modern Protestant missionary enterprise. At the same time, the idea of empire was evolving into a concept of a benevolent project of spreading culture and religion (which was used as a justification for all sorts of awful things).

That was the seed of my book. I look at how the Romantic epic revival reflects and even interrogates or challenges that evangelical turn of British imperialism. Writers could use the ancient genre of epic poetry variously to support, critique, or oppose developing ideologies of imperialism.

[PR]: Can you explain a little bit about the publication process?

[ML]: My experience publishing this book involved me practicing what I preach to my students about writing: I always say to classes, “Writing is a process of revision.” That is, writing happens in the revising. If you’re not revising, you’re not writing.

Over the years after I finished my PhD, I revised and expanded my dissertation. I made the opening chapter lengthier and more detailed; I added a chapter that surveyed more lesser-known epics of the period, and I even added a chapter that explored how Olaudah Equiano—author of one of the most influential slave narratives—drew on epic tradition in narrating the story of his life and opposing slavery. I also added an epilogue that reflected on the relationship between Wordsworth’s and Byron’s epics.

I wrote up a book proposal and shopped it around to publishers, and Cambridge University Press was interested right away. I sent off the manuscript, and then I had to wait for readers—all experts on British Romanticism—to peer review my manuscript. This was, by the way, right around the start of the pandemic, so that delayed things considerably. It took more than half a year for each reader to work through the manuscript and send me a report. The readers were encouraging, but they had more suggestions for revisions. So back I returned to the drawing board: writing is a process of revision, after all. On one reader’s advice, for example, I developed the epilogue into a full-blown chapter that explored Wordsworth’s and Byron’s epics in greater detail.

So, it took about three years from initial emails to acceptance of the final manuscript, and then it took another year of preparing the manuscript, copyediting, and finalizing everything. What an exhausting process.

[PR]: What are your hopes for its use and distribution?

[ML]: I made a deal with Cambridge University Press to make my book open access after it earns a certain amount. What that means is that once the book generates a certain level of profits, Cambridge University Press will make the book freely available on their website for anyone who wants to read it.

I did this because I want as wide an exposure of my work as possible. It’s my hope that researchers, literary critics, historians, and students will make use of my research and analysis, and will further explore the Romantic period and the history of epic poetry. One of the main reasons people do research and literary criticism is to advance human knowledge. I was only able to write this book because of the work that came before me, and I’m hoping in the future, my book will make it possible for future scholars to do their work.

So make sure to encourage your local libraries to purchase a copy!

[PR]: How many books have you written in the past?

[ML]: This is the first book of what I hope is many to come. Since it took me a decade to write and publish this book, I’m hoping to do the next one in five years. Fingers crossed.

[PR]: How does your work at the Mount relate to the publications you author?

[ML]: I see teaching and scholarship as interconnected. Scholarship makes us better teachers, and teaching makes us better scholars. To be a good scholar, you have to be a teacher: writing a book is, basically, teaching your audience what you learned about a topic. And to be a good teacher, you have to be a scholar, researching the most important findings about your subject so that you can convey this information to others.

When I teach literature, I often teach about Romanticism. I brought extracts from my book into the English senior seminar a few years ago (where we examined Romantic-era texts in context). I teach a course on “Frankenstein” every spring, and I may bring in some extracts to at least make students aware of the epic context of the period. Shelley’s novel is often discussed in terms of its relationship to epic: Frankenstein’s Monster actually reads “Paradise Lost” and compares himself to several of its characters. It’s common for critics to argue that Mary Shelley, in a sense, “rewrites” “Paradise Lost” to respond to Milton and the epic tradition.

I teach writing classes most often, and my book is, at its heart, about literary form: the way writers used the form of epic poetry—its conventions, devices, tropes—to respond to their age. That is, one of the key ideas behind my book is that a literary text’s “meaning” isn’t merely about its content, but about the form in which that content appears. This is just as true in students’ writing: grammar and sentence forms aren’t mere “rules” to be followed or “styles” to be adopted—they are inseparable from generating meaning. Teaching students to write well is a matter of helping them become aware of, and refine, their own use of form, and writing well about literature, in particular, is a matter of paying attention to how writers deploy literary form.

About the University of Mount Saint Vincent

Founded in 1847 by the Sisters of Charity, the University of Mount Saint Vincent offers nationally recognized liberal arts education and a select array of professional fields of study on a landmark campus overlooking the Hudson River. Committed to the education of the whole person, and enriched by the unparalleled cultural, educational and career opportunities of New York City, the College equips students with the knowledge, skills and experiences necessary for lives of achievement, professional accomplishment and leadership in the 21st century.